The machines emit a pencil beam that rapidly moves across and up and down the body, he said. Part of the trouble is that there is no ideal device for measuring the radiation dose given by backscatter X-rays, said David Brenner, director of the Columbia University Center for Radiological Research. Helen Worth, a spokeswoman for the Johns Hopkins lab, referred questions to the TSA. Although the device, known as an ion chamber, is commonly used to test medical equipment, they argue that the detector gets overwhelmed by the amount of radiation the backscatter deposits in a short time and might not provide accurate readings. The physics and medical professors also took issue with the device used to measure the radiation.

The researchers' names have been kept secret, and the report on the tests is so "heavily redacted" that "there is no way to repeat any of these measurements," they wrote. Instead, the tests were done on a model built by the manufacturer, Rapiscan, and configured to resemble a system previously tested by the TSA. In the most recent letter sent to Holdren on April 28, the professors note that the Johns Hopkins lab didn't test an actual airport machine.

#Sc body scannerz skin

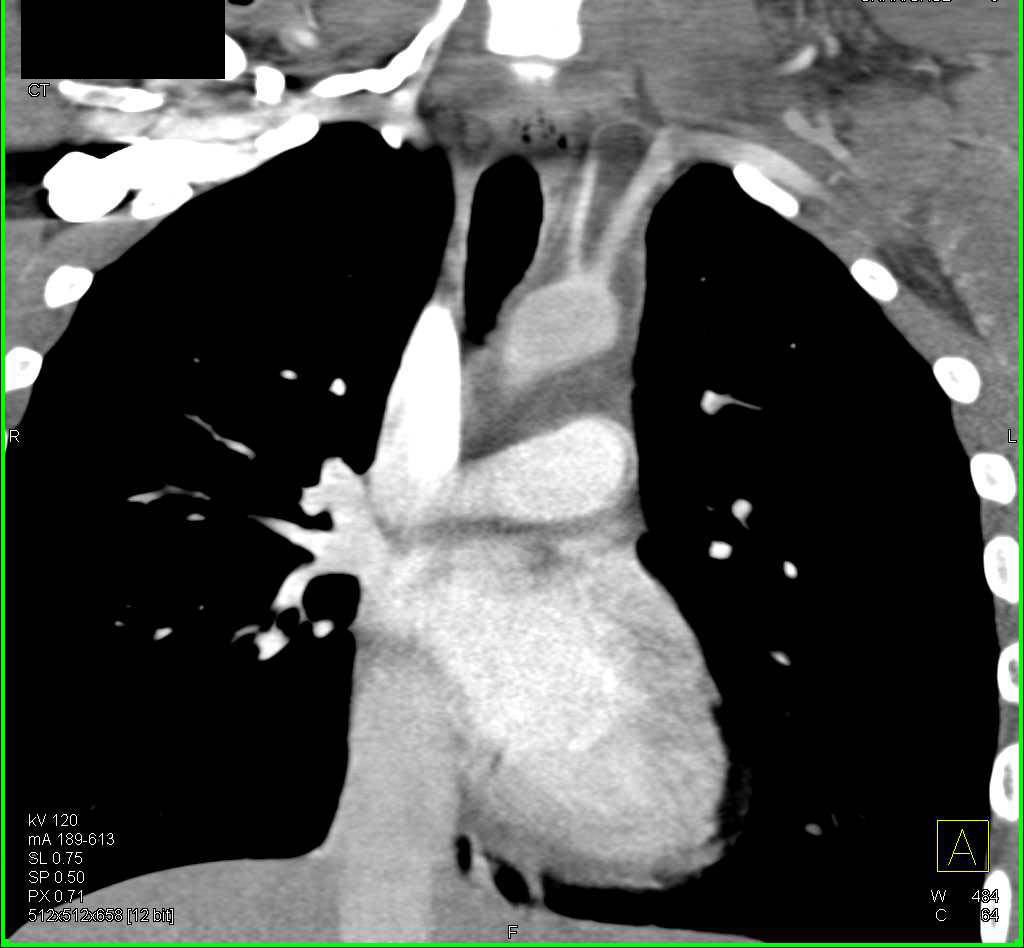

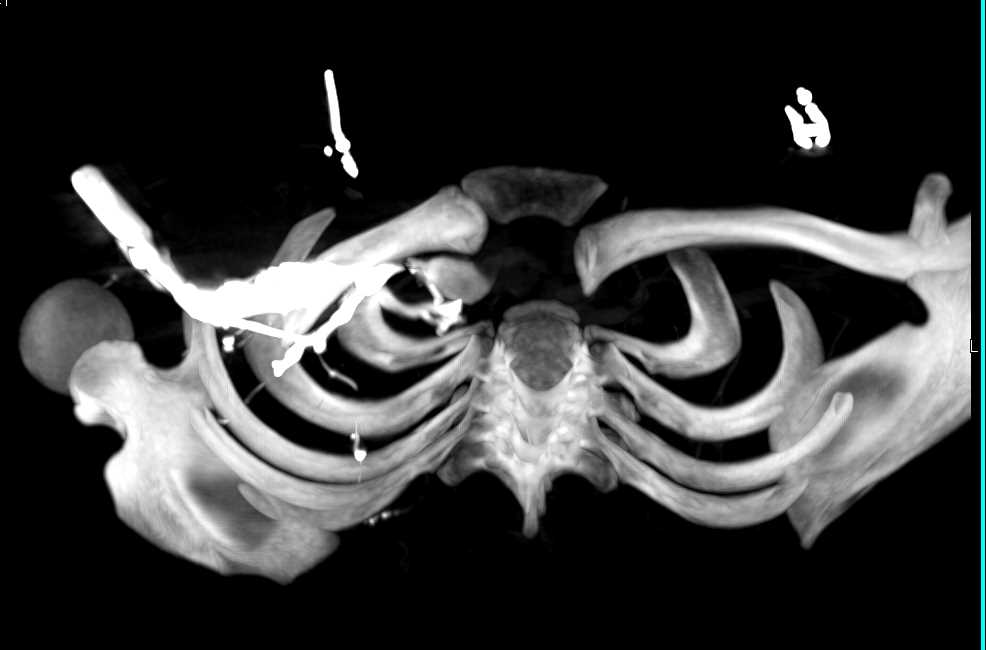

Last fall, FDA and TSA officials released a study that estimated the dose to the skin to be twice the dose to the body, though still extremely low. The same group stirred controversy last year when it sent a letter to Holdren arguing that while the overall dose to the body may be low, the TSA hadn't quantified the dose to the skin. "There's no real data on these machines, and in fact, the best guess of the dose is much, much higher than certainly what the public thinks," said John Sedat, a professor emeritus in biochemistry and biophysics at UCSF and the primary author of the letter. And they have been disturbed by the TSA's reluctance to do so. Studies published in scientific journals in the last few months have also cast doubt on the radiation dose and the machines' ability to find explosives.Ī number of scientists, including some who believe the radiation is trivial, say more testing should be done given the government's plans to put millions of passengers through the machines. The TSA says the results have all confirmed that the scanners don't pose a significant risk to public health.Īccording to the agency and many radiation experts, the dose is so low, even for children or cancer patients, that someone would have to pass through the machines more than a thousand times before approaching the annual limit set by radiation safety organizations.īut the letter to the White House science adviser, signed by five professors at University of California, San Francisco, and one at Arizona State University, points out several flaws in the tests. Survey teams are using radiation-detecting dosimeters to check the machines at airports. The TSA says the backscatter technology has been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institute for Standards and Technology and the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Because the beam doesn't go through the body, most of its radiation is received by the skin. In the latter, the rays bounce off the skin and create a fuzzy white image of the passenger's body. Backscatters work like a fast-moving X-ray.

Millimeter wave machines emit a radio frequency similar to cellphones.

#Sc body scannerz software

A software programmer warns a screener, " If you touch my junk, I'm going to have you arrested."Īfter the underwear bomber tried to blow up a Northwest Airlines plane on Christmas Day 2009, the TSA ramped up deployment of full-body scanners and plans to have them at nearly every security line by 2014. They are also important for TSA's public relations battle over the alternative, the "enhanced pat-down," which has bred an epidemic of viral videos: A 6-year-old girl is touched from head to toe. The machines, which are designed to reveal objects hidden under clothing, have the potential to close a significant security gap for the TSA because metal detectors can't find explosives or ceramic knives, which can be just as sharp as the box cutters that hijackers used on 9/11. And in a new letter sent to White House science adviser John Holdren, they question why the TSA won't make the scanners available for independent testing by outside scientists. The company that makes them says it's safer than eating a banana.īut some scientists with expertise in imaging and cancer say the evidence made public to support those claims is unreliable. The Transportation Security Administration says its full-body X-ray scanners are safe and that radiation from a scan is equivalent to what's received in about two minutes of flying.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)